The Sun God Shamash in Ancient Mesopotamia

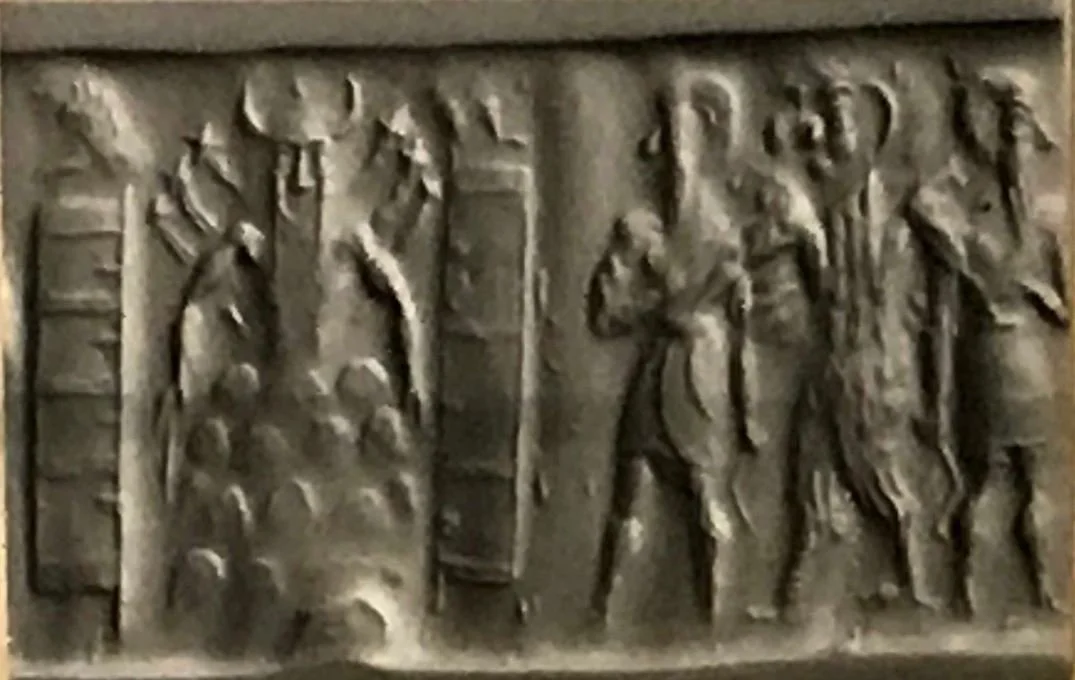

Among some of the strangest archaeological finds on record is those of the ancient Babylonian and Sumerian societies. There are a set of images which describe a most peculiar scene that at first glance looks highly technological. In the image below, we see what appears to be a man dressed in a suit of armour, standing inside a contraption of some sort surrounded by doors. At his feet we see what appears to be smoke rising up, and rocket-like structures coming off his back. Other people stand by watching on. They all are holding a tool of some form, perhaps something like a ratchet for the purpose of operating the contraption. The image is from a Cylinder Seal dated to 2340 - 2200 B.C. What exactly is going on here?

This image, and others like it, is what drew me into an interest in Near Eastern studies, which is largely in the area known as modern day Iraq. To study them, I set about visiting every Near Eastern collection at any University in the world I could find which had artefacts, and I photographed everything. I literally have thousands of photographs of Mesopotamian objects. I was drawn into this most mysterious culture, which often gets neglected among the heightened interest of Egypt, Rome and Greece. Indeed, it is curious that we are not taught about the Mesopotamian cultures in our Schools.

When one examines this image for the first time, one is forced to speculate on whether we are looking at a potential flight capability here. Is this image, we see what looks like a man, perhaps a solider, about to take off in some kind of self-propelled human rocket suit? I became so interested in this, that I enrolled on Mesopotamian academic courses and built up a large collection of old and new books on the subject. Although I am yet to learn Cuneiform, the ancient written language of these people, I did get as far as learning how to transliterate proto cuneiform, which is fun, if not challenging. So, I think it is useful to properly describe what I have discovered about these images and ones like it and what exactly we are looking at here according to the interpretation of modern scholars. In particular, why it in fact does not depict a man in flight despite appearing to do so.

Throughout history, humans have worshipped the Sun, Moon and stars as well as other planetary bodies. The ancient Greeks and Romans went as far as assigning gods to each of the planets of the known Solar System. The ancient Egyptians even had Horus as the god of the sky and Ra as the God of the Sun. The Mesopotamians were no exception and in this article we will describe the Sun-God Shamash in Akkadian but also known as Utu to the Sumerians. He is often recognised by a version of an ancient star or sun symbol or a solar disc. It is Shamash that is depicted in that image above, and in fact he is seen to be rising out of the mountains as a representation of the Sun at dawn.

Symbols of Shamash the Sun God

Shamash is the brother of Inanna. He is the son of the Moon God Nanna or in Sumer the fertility goddess Ningal [Ref 1]. Research does not lead to a firm conclusion on who his father was. He is shown with streams of fire coming off from his upper arms and shoulders, somewhat similar to how fine filaments of plasma are often observed emanating from the surface of the Sun. These are controlled by magnetic fields and have the appearance of rivers of fire flowing away from its surface. Shamash has a long beard and is also depicted wearing the horned crown of divinity and in his left hand he holds a long saw-toothed knife like a pruning saw for the purpose of cutting his way through the mountains so he can rise up in the mornings dawn (sunrise) and goes down at dusk (sunset).

His clothing is typical of dress of other people in that era, a form of long striped skirt that goes down to his lower legs. He is also associated with the Netherworld (also known as the Great Dwelling [Ref 2]), but during the day he brings light and warmth to the lands below which he travels over. This is important for the function of agriculture. During the night when he disappears in the West it is assumed that he has gone to sleep.

The specific subject of interest in this article is how Shamash is depicted visually and often on these cylinder seals. He is often shown behind a set of stylised doors (known as the portals of the dawn) operated by attendant gods (called gate keepers) each surmounted by a Lion and a Lioness on top, who upon opening the doors will see a vista of distant mountains. These are likely the Zagros Mountains since the Sun rises in the East and the images often show Shamash rising out of the mountains towards the hemisphere of the sky which is the residence of the gods.

The Twin Peaks of Mount Ararat and the Araratian plain Through Which Shamash Likely Rises (photo credit: Serouj Ourishian

The Zagros Mountains are in modern day Northern Iran and South-Eastern Turkey. They have a length of 990 miles and a width of approximately 150 miles, and at their peak elevation rise to 14,465 ft. Often Shamash is depicted rising between two twin mountain peaks and these may have been the twin peaks of Mount Ararat known as Greater Ararat and Little Ararat in Turkey which rise to an elevation of 16,849 ft and 12,779 ft respectively. This is curious because an examination of a map shows that Mount Ararat is located approximately 600 miles from say the ancient Sumerian city of Uruk at a position of around North-North-East. This would mean that it can only rise in between the peaks during the winter, since in the summer it would rise much further to the right of the mountains. Speculating, this may have been one of the ways that the people from ancient Sumer kept track of the yearly solar cycle through the rising of Shamash between the peaks of this mountain range.

In terms of the Sun setting into the West there are no mountains but desert which stretches into modern Saudi Arabia. During the winter Shamash would have set into the South-West-West direction (further East) and during the summer into the North-West-West direction (further West). The nearest large mountain range would be the Hijaz and Asir Mountains close to the coast of the Red Sea which is beyond the visible horizon of ancient Mesopotamia. The Sinai Mountains of Egypt are also beyond the visible horizon. So, Shamash would have mostly set into a flat horizon - unlike the rising in the East. We must therefore conclude that the cylinder seal depictions of Shamash pertain solely to his rising in the East, and by implication perhaps there is no gate into the Netherworld towards the Western setting of the Sun.

The ancient Mesopotamians often used cylinder seals to put down important information about trade contracts, records of agricultural stock, general accounting of items or to depict scenes from their society and mythology. They were used from around 3400 B.C for over three millennia. These are made by pressing a sharp wedge-shaped implement into a cylinder stone of various different materials such as greenstone, serpentine and hematite. These can then be worn around the neck by inserting a thread through its central hollow column or press rolled onto wet clay to show an image of the seal. In the following figures four-cylinder seals are presented which give an insight into the function of Shamash in ancient Sumer.

In the figure below [Ref 3] we see him using his knife to cut away at the mountains and fight his way to the dawn. Others are showing perhaps waiting for the rising Sun, to include Enki with his rivers of fish and Ishtar who is preparing to hunt with her bow, Lamasu as a hybrid flying bird, the two faced Usmu who serves as the messenger of Enki.

Greenstone Cylinder Seal, by a scribe named Adda, with Shamash shown cutting through the mountains on the horizon so he can rise at dawn, Southern Iraq, ca.2300 BC, Akkadian, British Museum, London, No. ME89115. [Credit: K. F. Long].

In this figure [Ref 4] Shamash is fully risen and is stepping on top of the mountain beginning his day-long trek across the sky. Cuneiform symbols are also present and discussed further below. We note the difference in height between the two mountains consistent with the two peaks of Mount Ararat. The attendant 'gatekeepers' are also shown to control access.

Serpentine Cylinder Seal, Shamash rising on the horizon to bring the golden dawn, flames of fire ascending from his shoulders, Southern Iraq, ca 2300 BC, Akkadian, British Museum, London, No. BM89110. [Credit: K. F. Long].

In the next figure [Ref 5] the description at the Louvre states that Shamash has now had his sunset behind the mountains of the West. However, as described in the above assessment of the mountain ranges this doesn’t quite fit since there are no mountains to the West, so instead perhaps the image may depict Shamash in his full glory, perhaps at the high-Sun point of the morning around midday. Indeed, this could be a similar depiction to that of the Egyptian god of the Sun Ra who is often identified primarily with the noon Sun.

Serpentine Cylinder Seal, Shamash has his sunset and disappears behind the mountain of the West, Sumer, ca 2340-2200 B.C, The Louvre Museum, Paris, No. AO2280, The Louvre Museum, Paris. [Credit: K. F. Long].

Finally in the final figure [Ref 6] we see a seated figure within the mountain that historically archaeologists believed to be Shamash, but this is also believed to be a separate god of the underworld known as the bull-man Nergal (who is the consort of Ereshkigal the Queen of the Netherworld). On the left of the image, he has been defeated in battle, and he is depicted burning inside the mountain whilst an attendant of Shamash lights the fire with a torch. On the right of the image he is inside the symbolic mountain of the underworld locked up with his mace shattered in defeat. This imagery is important since it illustrates that Shamash acts as the gateway between the world of the living and the world of the dead.

Hematite Cylinder Seal, showing Victory of Nergal, god of the underworld, Akkadian, Babylonia, ca 2340-2200 BC, The Louvre Museum, Paris, No. AO2485, The Louvre Museum, Paris. [Credit: K. F. Long].

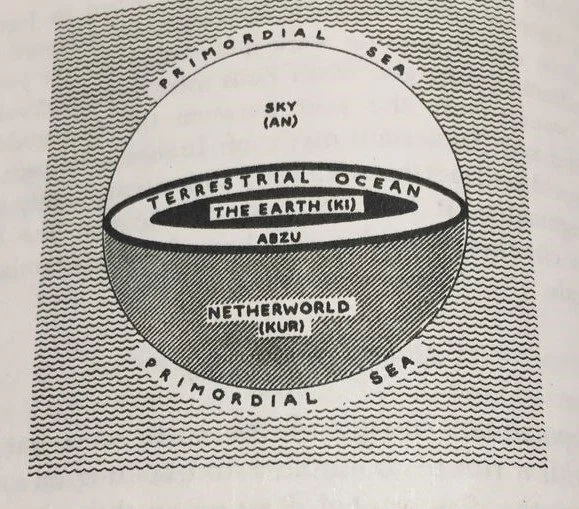

The people of Sumer had a cosmological model for reality which appears to be simpler than the models we have developed today. It was essentially two-sided with one half occupied by the living and the other half occupied by the dead, although both domains were ruled by the gods. However, it was possible for the living to interact with the dead through a kind of bridge or tunnel (an 'erech' [Ref 2]), which facilitated the joining of the two realities. At the entrance to this tunnel was a gate, and it would not be inappropriate to refer to this as a form of Stargate, since it was through these gates that the Sun and the Moon would pass. Indeed, we learn that when there was a new moon it was considered that the Moon was taking its day of rest in the Netherworld.

Sumerian Cosmological Model

During the daytime Shamash would rise high into the sky above our heads, moving from East through South towards the West, and this was believed to be him travelling in his Sun Chariot. This also allowed him to observe the world below and the coming and goings of people and so to utilise his divine justice or divine compassion when required. For this reason he can be thought of as an all seeing Omniscient God during the day.

The purpose of Shamash within the Netherworld was to assist the spirits of the dead through a tunnel towards his abode at the extreme western end of the world where the Sun set. Thus, whilst the rising of the Sun represents the re-birth of the world, the setting of the Sun represents the world of the dead. Shamash was important for the people of the living since he afforded an opportunity for them to take care of their ancestors who were dead on the other side, living in dreadful conditions with only dust to eat and dirty water to drink [Ref 7]. These could be provided by the living and facilitated for the dead within the netherworld by Shamash who controlled the gate; music and festivities may have played a role in this process.

In general, it is not possible to travel back through the gate from the dead to the living, and the goddess Inanna is the only one to have ever achieved this [Ref 8]. But if you did, then strict regulations must be observed including wearing no clothes [Ref 2]. Any festivities associated with an interaction between the living and the dead by a temporary joining with the Netherworld would presumably come to a head at the rising of the dawn when Shamash is able to open the gate.

Shamash features in the Epic of Gilgamesh [Ref 9], as Gilgamesh goes on a journey eastward to find Utnapishtim who the gods made immortal. He firstly makes his way towards the Cedar Forest. He finally arrives at two high mountains called the Twin Peaks "their summits touch the vault of heaven, their bases reach down to the underworld, they keep watch over the sun's departure and its return" [Ref 9]. There the scorpion man tells him that "no-one is able to cross the Twin Peaks, nor has anyone ever entered the tunnel into which the Sun plunges when it sets and moves through the Earth" [Ref 9]. Gilgamesh is told that he has 12 hours to run through the dark tunnel as fast as the wind before the Sun sets and enters. In some versions of the Epic Shamash is said to set over the twin peaks of Mashu. In the poem Inanna's Descent to the Netherworld it states that within the Netherworld there is a place described as a 'lapis lazuli mountain' [Ref 2].

In some ways Shamash at the rising of the Sun is similar to the Hindu god Vishnu the preserver and at the setting of the Sun is similar to Shiva the destroyer. Together these are a part of the three-form Trimurti since they are connected by Brahma the creator. Similarly, it could be argued that the Sumerian cosmology is also a trinity since the dead and the living are connected by the bridge or gate that is facilitated by Shamash. This similarity may not be a coincidence given that Mesopotamian cultures conducted trade with the Harappan cultures in the Indus Valley [Ref 10] which borders modern day Pakistan and India and with trade often comes a sharing of ideas which can work either way.

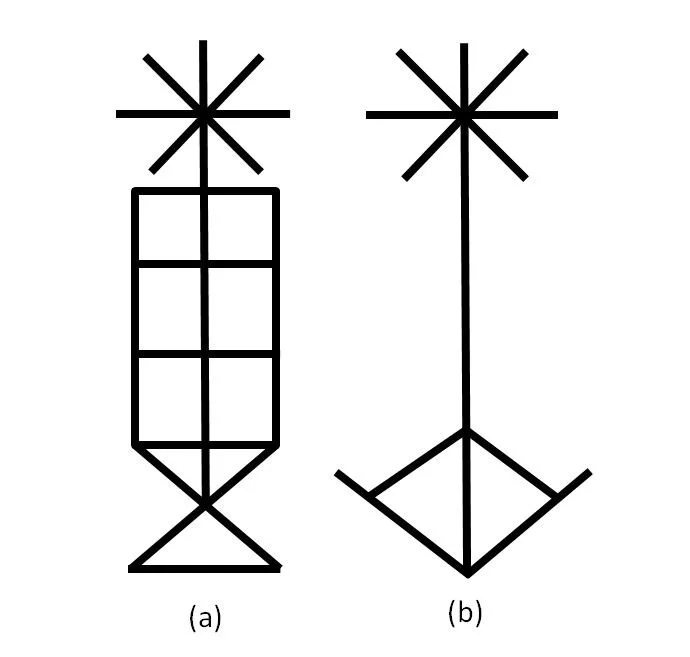

Finally, we note the Cuneiform symbols for Shamash which featured in the second cylinder seal image above an is also shown below. Although called Utu in Sumerian he is also known as Samas which is made up of the Akkadian logogram. Samas comes from the Akkadian word for Sun Samsu [Ref 11]. The figure below shows a symbol for the Sun but on top of a grid-like symbol, which speculating may be the symbol of the scribe responsible for describing the journey of Shamash. The right hand figure below appears to depict a 'star spade' and it has the appearance of the Sun rising up on the end of a spade since Shamash is cutting his way to the dawn. However, the lower part of the symbol is also very similar to the Cuneiform symbol for 'day' and so this may signify the rising of the Sun for a new day (Utu-e3) [Ref 12] as Shamash awakes.

Cuneiform symbols (a) a star and grid shape (b) a star spade.

The Sumerian cosmology was fascinating and how they saw their gods intimately linked to the celestial objects in the sky. It was the basis of our first astronomy and yet they appeared to have a sophisticated understanding where the Sun, Moon and Planets were given a real personality, character and role. Our version of what the cylinder seals really meant is part speculation, but it is our best guess after centuries of studying these unique artifacts, which on face value, appear to be highly strange and it is no surprise to those who may not be familiar with the traditions of this ancient culture to misinterpret what they are seeing.

Yet, when looking at the images of Shamash, it is difficult not to impose our modern knowledge of technology on to their depictions and at least ponder the possibility that the ancients may have mastered flight and that perhaps, it is our interpretation that is wrong. One might be attempted to adopt this interpretation since there are other depictions in the Near East that also point towards a flight capability, such as with how Zoroaster in Zoroastrianism is also shown in what appears to be a winged vehicle. This would be pure speculation of course, yet it is fun to imagine such possibilities.

Unless evidence emerges to suggest otherwise, for the present we are left to the interpretation of archaeologists and those that perform the transliteration of this most ancient world. In that what we are seeing here is the depiction of the Sun rising in the East and setting in the West. In reading this article, I hope that like me, you never look at the Sun the same way again, particularly as it sets in the West on the horizon. For according to the Mesopotamian beliefs, it is the land of the ancestors and where we go when we die.

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utu (last accessed 15 June 2021).

S N Kramer, The Sumerians, Their History, Culture, And Character, The University of Chicago Press, 1963.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W\_1891-0509-2553 (last accessed 15 June 2021).

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W\_1873-0901-1 (last accessed 15 June 2021).

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010147553 (last accessed 15 June 2021).

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010149674 (last accessed 15 June 2021).

K Kelly, The Netherworld, Death and Burial, The First Civilization: Mesopotamia 3500-2000 BC, University of Oxford Distance Learning Course, June 2021.

Inana's Descent to the Nether World: Translation, The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr141.htm (last accessed 15 June 2021).

S Mitchell, Gilgamesh, A New English Version, Profile Books, 2005.

H Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians, Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

ref. oracc.museum.upenn.edu/amgg/lisofdeities/utu (last accessed 15 June 2021).

J A Halloran (Editor), Sumerian Lexicon, A Dictionary Guide to the Ancient Sumerian Language, Logogram Publishing, 2006.